Like the shifting sands of the ocean itself, the Avalon city council is weighing a variety of options and cost estimates presented to them by experts as they struggle to find the funds to shore up South Beach and other coastal problems.

And ironically, it seems that the prosperity that arrives each day on the jet powered ferries may be also bringing with them “prop wash” that is suspected of blowing the sand away from South Beach.

Representatives of Michael Baker International were on hand this past week to present the options to the council, which included options of dredging sand from the bay and replacing the lost sand and long-term strategies to keep the sand from migrating in the future.

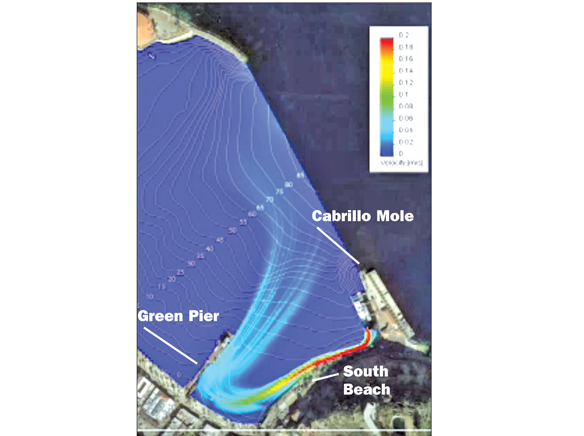

In short, Dr. Scott Jenkins said while wave patterns, ocean trends and other factors contributed to the erosion of South Beach, computer modeling indicated that reverse thrusters on jet powered ferries pushed the sand around the bay as much of it is being deposited under the Green Pier.

Remnants of piers from the steamship era and pilings holding up the pier provide a perfect depository for the suspended sands as the jet thrust and currents push them in a semi-circular fashion as the force bounces off the seawall, said Jenkins.

More than 5,000 yards of sand has been displaced over time, said Jenkins, after which he detailed an “intervention strategy.”

Jenkins said their calculations were based on “computational fluid dynamics” to make their determination and that the big boats have to run their thrusters to ensure stability as passengers embark and disembark.

City officials and Baker representatives claimed to have met with the ferry companies and other boat owners and that they were cooperating in every way but must ensure safety of the passengers.

Baker representative Makrom Shatila said Avalon needs a “two-step process” to remedy the situation, adding that the damage had “occurred over decades” and that solutions would “not happen instantaneously.”

The engineers suggested to the council that any sand placed back on the beach should be “native” to Catalina should it be dredged up using suction and other equipment in the bay.

Shatila said to replace the sand, it will likely be necessary to dredge 9,000 yards to get 6,000 yards back on the beach.

City Council Member Pam Albers sharply questioned early estimates of the dredging of the sand which was initially estimated to cost $20 per ton and which is now estimated to cost north of $100 per ton.

If this was the case, she said, the dredging project cost would amount to $1.3 million and “we don’t have that kind of money,” she told Public Works Director Bob Greenlaw.

Taking all of the various proposed seawall and restoration improvements, she said, “We just don’t have the money to do all these projects.

Albers floated the idea of seeking a grant from the California Division of Boating and Waterways to which Greenlaw responded even if successful among tough competition, the funds wouldn’t be available until 2022 at the earliest.

Greenlaw said South Beach restoration is a “must do” project and urged the council to allow the public works department to continue working on an engineering Request for Proposals.

Mayor Anni Marshall expressed support with moving forward with the dredging, saying at least they will get engineering data while all of the other solutions are being debated and funds are being sought.

Council Member Cinde MacGugan Cassidy said she had received the latest study results “less than 24 hours ago” and urged the council not to make any immediate decisions.

She also questioned whether Baker had reviewed all earlier dredging and harbor studies, which they said they had done.

MacGugan-Cassidy said she needed more time to study the data before “making million-dollar decisions.” She also questioned whether one major “winter storm” could negate all of the dredging work by again washing away the sand. Jenkins said no.

Once the sand has been replaced, the engineering firm suggested a number of options for Cabrillo Mole improvements to mitigate the need for the ferries using their reverse jet thrusters or structures to deflect them away from South Beach.

The three major alternatives included:

• A series of ‘dead man’ pilings and floating docks and resistance weights.

• A barrier wall to divert the thrust from reaching the beach.

• An innovative concept to literally add a new retaining wall large enough for restaurants and commercial establishments that would also accommodate the ferries and prevent the thrusts from reaching South Beach.

The council agreed to take no action but also did not revoke earlier authority for Greenlaw to continue working on an outline for an engineering RFP for the harbor projects.

Longtime resident Phil Hernandez took advantage of an opportunity to speak after listening the presentation.

“I’ve lived here all my life,” he said as Fernandez passionately asked the city to restore the “fingers” on the mole that used to protect the sand. “We’ve messed ourselves up,” he said, and the costly project being discussed “is not going to work, just going to move a little sand around.”

“Put those fingers back in there,” he said, a view also bolstered by resident Carl Johnson, who also spoke to the Council after the discussion. “We need to fix those fingers,” which he said “were doing a very good job for a very long time” before they were damaged and never repaired.