While California regulators are still struggling to come up with an equitable way to drastically reduce the carbon emissions of commercial harbor craft, the industry awaits their fate and are doing their best to mitigate the rules they believe will be enacted soon.

In an interview with Bonnie Soriano, Transportation Section Chief and David Quiros, who directs the Freight Division, both with the California Air Resources Board (CARB), they both acknowledge the difficulty of implementing the regulations but say they are ultimately necessary for the state to meet its future emissions targets.

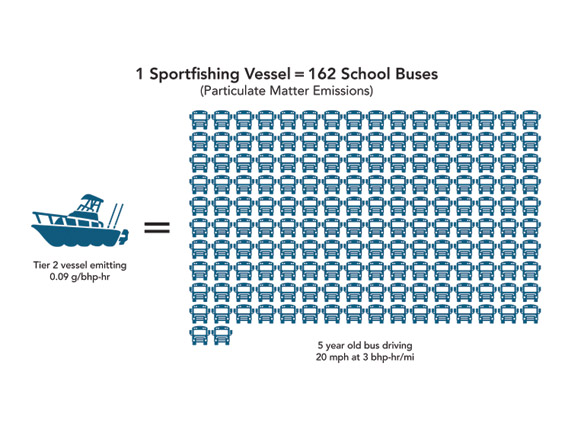

The image above illustrates the volume of air emissions put out by a single sport fishing vessel, according to the state Air Resources Board.

At issue is the potential to drastically reduce toxic emissions emitted by commercial harbor craft, as officials from the CARB are seeking to eventually mandate all commercial harbor craft to update engine technology (from so-called Tier 2 to Tier 4 technology).

While engine emission technology on most ground transportation vehicles has evolved over the years, engines for commercial harbor craft have evolved less slowly, officials say.

An example listed on the agency’s website, one sportfishing vessel, with a Tier-2 diesel engine, which is generally today’s standard, emits more particulates into the atmosphere than approximately 162 five-year-old school buses driving 20 miles per hour.

“School bus engines that are on the road today have had an accelerated process of becoming lower emission,” said Soriano.

“And so are the emissions for an on road truck for example,” she said, noting that ”they’re significantly cleaner than marine engines.”

As a result, said Soriano, the marine industry standards have lagged far behind the emission standards of most ground transportation methods.

“Diesel emissions are toxic substances,” she said, “whether it comes from a school bus or a truck or a ferry or a fishing vessel.”

“It’s just that the emission levels of marine engines are so much higher than they are for on-road vehicles, and even other off-road categories,” said Soriano.

“They [engines] just have not kept pace in terms of stricter engine standards with some of the other on-road and off-road categories,” she said.

There are several types of harbor craft in California, including fishing vessels, ferries, excursion vessels, tugboats, tow boats, crew and supply boats, barges, dredges, and other vessel types, she added.

CARB has regulated commercial harbor craft since 2009. By the end of 2022, the Current Regulation will require Tier 2 or 3 engines on a subset of harbor craft (excursion vessels, ferries, tugboats, crew & supply vessels, barges, and dredges).

The final wording of the proposed amendments, which the agency says they have been actively working on since 2018, are anticipated to be released soon. After final approval by the board, the new regulations could take effect as soon as 2023 and are designed to drastically reduce commercial harbor craft emissions.

“We are in the process of a rulemaking for harbor craft that includes tugs, sport fishing vessels, ferries, work boats and 18 different categories of vessels that we … included in the regulation,” said Soriano.

Traditional recreational craft are unaffected, they added.

Soriano said the staff presented data to the board back in 2018 that illustrated the high emission rate of harbor craft “showing that the harbor craft are one of the three top source categories that contribute to cancer risk and other air pollution from port sources.”

So, she said, “the board directed us to come back with amendments to provide additional reductions from the harbor craft sector,” said Soriano.

According to CARB’s website, the new regulations are projected to reduce toxic commercial harbor craft emissions as much as 89 percent by 2035.

While the entire industry will be affected statewide, Catalina Island, especially Avalon, is watching developments carefully.

The CARB executives say they have been visiting some harbor craft companies to get feedback and input, speaking to others (via Zoom) seeking to mitigate the impact.

Greg Bombard, president of Catalina Channel Express said in a follow up interview this week that while CARB has not visited the company in person, they have held several Zoom calls with CARB staff.

Catalina Channel Express, a fleet of eight ferry boats that carries islanders and tourists to Avalon every day of the year, will be significantly affected by the new regulations, said Bombard. He too said he is curious to see the final version of the pending regulations.

Moreover, he continues to say that if there is no external funding attached to the new regulations, concerns grow about their business going forward, or more likely, what rates will look like in the future.

Already, they are appealing for a short-term fuel facility that will allow them to recover the massive expense of high fuel prices, said Bombard. “At current levels, we estimate the skyrocketing fuel prices will cost the company $5 million this year.”

Even though Catalina Express is a private company, Bombard said their role in the health, welfare and safety of Catalina Island qualifies it as a public ferry operation.

Regarding the Tier 4 engine upgrades, if required by the new CARB rules, Bombard said the company is not opposed but is asking for a funding solution.

“We are not asking for the state to fund the entire amount,” said Bombard this week. “We are prepared to invest our own money, but we believe it is a shared responsibility to meet new emission standards.”

“I’m not out to fight them [CARB],” he said, “I’m just saying we need help. We don’t disagree with what they are trying to do.”

Bombard says his current fleet is currently compliant with Tier 2 engines, but if the new regulations require his entire fleet to be upgraded with Tier 4 engines, it is estimated to cost the company $120 million, saying the new engines are too large and heavy to fit in the current engine bays.

“We would have to make twice the number of round trips to carry the same number of passengers,” he said. “That is not cost effective,” he said.

A straight up loan of $120 million could significantly increase, if not double the ticket prices, he said. That won’t work either, he added.

Complicating the issue even further, Bombard said the electric engine technology to produce the amount of torque necessary to have a Tier 4 [near zero emission] electric engine large enough to power the larger ferries “simply does not yet exist.”

In addition, he said currently, there is no guarantee that even if the fleet was completely upgraded with current technology, that the agency would not come back when the technology improves to upgrade once again.

When Bombard’s question was posed to CARB, they responded with the following email statement:

“Our current proposal evaluates costs and emissions benefits through 2038; however, the Board Resolution could direct staff to continue to evaluate the progression of cleaner technologies, such as zero-emission, and return with amendments that could take effect before 2038.”

“Any future regulatory efforts would consider the incremental costs and emission benefits of further regulation, which would consider any capital investments incurred under the Proposed Amendments.”

“We are not able to make guarantees about future actions/requests of our Board to further tighten controls if technology progresses more quickly and it is cost effective or beneficial to public health to adopt cleaner controls,” CARB officials said in an email statement issued by Public Information Officer Lynda Lambert.

In fact, Quiros, who directs the freight division, said he believes the board, when all is said and done, will have some funding opportunities for commercial harbor craft as part of the regulatory roll out.

“There are a number of incentive programs that are available to harbor craft,” he said, noting the Carl Moyer program has been used to fund turning over diesel equipment before the requirements of the current legislation took effect,” said Quiros.

In addition, he said there was also a demonstration grant program, and that there are bills currently in the state legislature (Assemblyman Patrick O’Donnell has filed a bill), and there is the Clean Off-Road Equipment (CORE) program.

Both he and Soriano said they believe money from the recently passed federal infrastructure bill, at some point, could become available as well.

“There may be future funding opportunities that are earmarked just for harbor craft reducing the cost to the operators to comply with the regulation,” said Quiros.

In addition, both CARB officials say there is a possibility of Catalina Express, or any potential company impacted by the new regulations to file an “alternative compliance plan,” which would allow them to partially comply with the regulations.

The “alternative” compliance plan would then allow them a period of seven years to allow more advanced technology, and financing, to emerge.

Lambert said in an email on March 17 that CARB is scheduled to discuss the new regulations at its March 24 meeting.

In the meantime, Bombard said his company, and others with similar interests, continue to discuss the final rules and regulations with CARB to find a workable path to reduce commercial harbor craft emissions.

In the end, he said, “I don’t think anyone is going to leave the island hanging.”